Why Canada’s Yellowknife is the Best Spot for Aurora Hunting

The night sky’s supernatural light display brings joy in the far reaches of Canada’s north.

When it happens, it’s like a god striking a match in the heavens. A green flame flares over the eastern horizon and then – suddenly, spectacularly – ignites into curtains of emerald light that billow in the midnight sky.

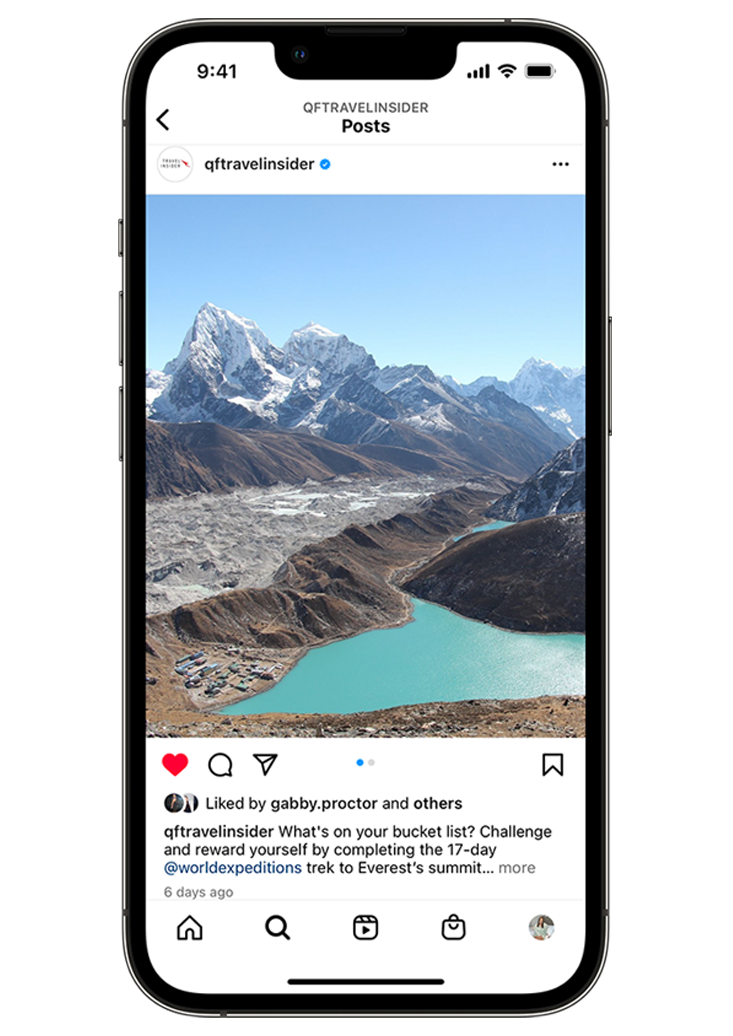

The aurora borealis is capricious and full of wonder. One moment it’s like fire, flaming into fantastic shapes – a chieftain’s headdress, a graceful manta ray swimming in a sea of stars. The next it’s wind, rippling and swirling as if propelled by air, and then water as liquid forms iridesce above me and, moments later, electricity pulsing with supernatural energy. Whatever form they take, the Northern Lights are never anything less than astonishing.

Chasing the aurora is an exercise that defies reason and, perhaps, sanity. I’m standing on frozen Lake Blachford in Canada’s northern wilderness, just shy of the Arctic Circle, in February. It’s almost 1am and -40°C – minus 40! – yet I’m staring dumbstruck at the heavens.

These are the most extreme conditions I’ve found myself in but a necessary sacrifice, I think, to understand what compels us to venture to the planet’s extremities in search of – what? Awe? Reverence? Joy? All of the above.

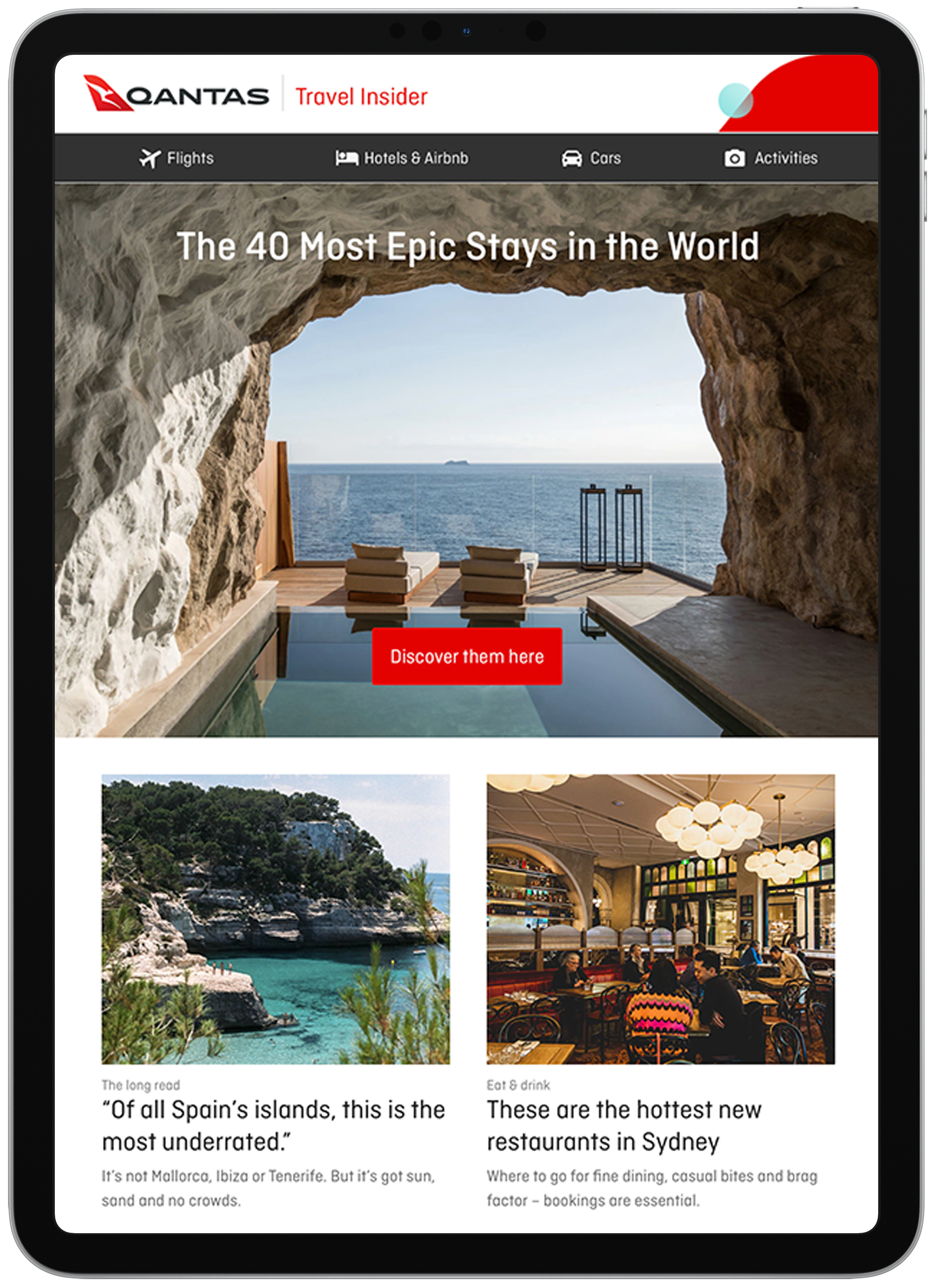

Staying at Blachford Lodge is hardly a sacrifice anyway. True, it’s in the middle of absolutely nowhere in a frozen Narnia world that’s startlingly beautiful and also unfathomably cold for an Australian. But for three nights in the northern winter, there’s nowhere else I’d rather be. The two-storey lodge has six upstairs suites and another five log cabins – including mine, the original but very comfortable Trapper’s Cabin, circa 1981 – nestled in spruce forests. The recently renovated spaces are furnished with plump leather sofas and pillow-top mattresses and decorated with objets d’Arctic including a bison head, First Nations carvings and framed photographs of the frozen north. The nine staff, comprising five winter-hardened Canadians and four French adventurers, provide exceptional, fuss-free service.

Chef Yves Page prepares meals that feel extravagant in such a remote setting, from daily brunches with freshly baked pastries to hearty lunches of soup and, for dinner, prime Alberta beef tenderloin with a classic crème brûlée to finish.

In winter, the frozen lake doubles as an airstrip. A 25-minute bush plane flight from Yellowknife, the capital of the Northwest Territories, Blachford Lodge is an adventure playground where guests ski, fish through holes in the ice and even hone amateur snow-masonry skills building a wonky igloo. The aurora appears every night I’m at the lodge including, on the last one, waves of green fibrillating above our firelit igloo. It’s an unforgettable sight.

Successful aurora chasing involves a huge amount of luck no matter which continent you’re on. If you want to increase your odds, Canada’s Northwest Territories are arguably the best bet. Located less than three hours north-east of Vancouver by air, Yellowknife (with a population of 20,000) has a clear advantage when it comes to viewing the Northern Lights. It sits directly beneath the Auroral Oval, the band of maximum activity. Local lore says it’s possible to see the Northern Lights here 240 nights of the year. Spend a few nights in the city and it’s said you have a 98 per cent chance of catching the show.

The odds work out for me. I’m staying at The Explorer Hotel, a popular base for daytime excursions (city tours, dog-sledding) and after-dinner light-chasing escapades. One evening, at 9pm, I board a bus to Aurora Village, 20 kilometres outside town, to find a magical-looking arrangement of 21 illuminated, fire-warmed teepees on the edge of a frozen lake. It’s an aurora theme park swarming with hundreds of people and, like Disneyland, has the potential to be the happiest place on Earth. If the lights come out. Which they don’t this night.

Fortunately, I have another shot at glory with Joe Buffalo Child, an Indigenous Dene guide whose ancestors have observed the lights for tens of thousands of years. Oral historians and gifted storytellers, the Dene refer to the aurora as yaké nagas (“the sky is stirring”). “It represents the spirits of our ancestors,” says Buffalo Child as we stand on Prosperous Lake outside Yellowknife beneath a brilliant half-Moon. “I was told by my grandmother that when the aurora is dancing and moving so fast, that’s when a close friend or a family member has just recently passed away. It’s a comfort. It’s a message of goodwill from the other side... [saying] ‘I’m over here and I’m okay.’ It’s nothing sad.”

Buffalo Child styles himself as an aurora “hunter”, covering up to 200 kilometres a night with guests in pursuit of his elusive quarry. En route in his truck-like Acadia SUV, he explains how the Northern Lights are caused by solar-powered magnetic storms that fill the sky with luminous colour as they strike oxygen and nitrogen in the atmosphere. His grandfather taught him how to read the sky and the weather. He thinks maybe he has a connection to the aurora. “I just get a feeling,” he says as the faintest streak of green appears above Prosperous Lake.

On a hunch he takes us to another lake, this one with low hills around its edges and a bitter wind chill. We’re admiring the Moon and Venus and cursing the cold when the aurora abruptly dances to life in the east. White to the eye, green through the smartphone. Magnificent either way.

Later, huddled in his heated vehicle waiting for more signs of extraterrestrial life, Buffalo Child lets me in on a secret. “Kendall, are you ready for this? The warmer the weather, the better the aurora,” he says with a laugh. “Ninety five per cent of the websites out there say winter is the best time. It’s not true! August 15 to the end of September – six weeks – aurora every night! And it’s more colourful, more vibrant.”

Now he tells me. I have zero regrets. These have been some of the most memorable nights of my life. But next time I’m coming in September.