Why the Future of Australian Design Is Actually a Return to Its Roots

As Australia grapples with rising building costs, climate pressures and a renewed respect for place, bold, thoughtful solutions are shaping our homes. From craft-driven materials and integrated furniture to First Nations-led concepts, a new era is emerging – one that values heritage, tactility and sustainability. Whether it’s a built-in banquette or a pattern book for houses, the future of design lies in making more with what we already have and doing it with care.

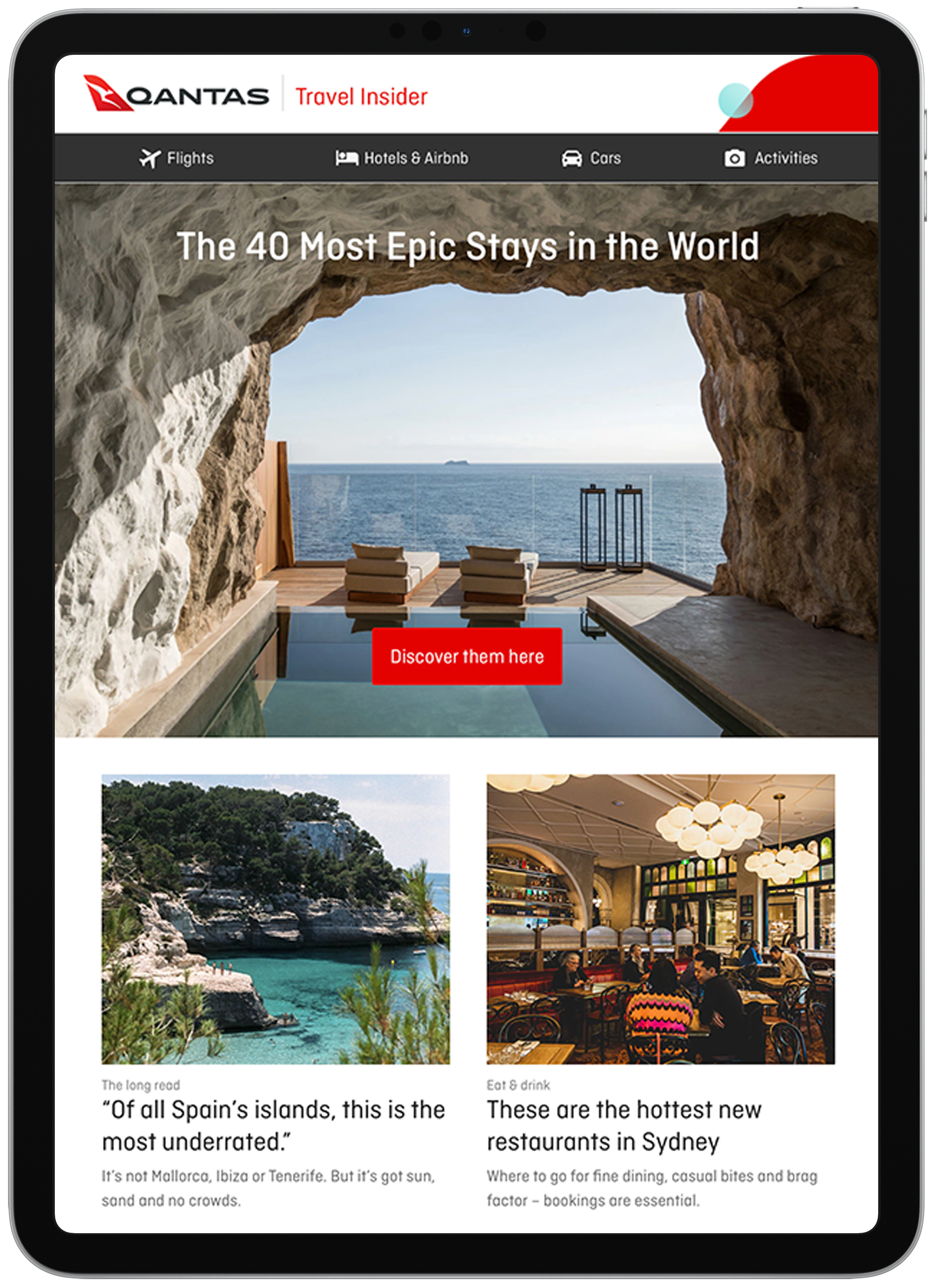

Elevated outdoors

“We used to just shove a bit of landscape around a building,” says Adam Haddow, a director at SJB Sydney and the national president of the Australian Institute of Architects. “Now it’s making a garden that happens to have a house in it.” He goes so far as to state that having a garden is more luxurious than having a bigger house. With the pressure on housing supply and the need to build smaller homes, architects are giving more thought to landscaping in new projects.

Sarah Lynn Rees, associate principal with Jackson Clements Burrows Architects, says that paying more attention to landscaping also establishes a better relationship of people with nature. “Every time we put a barrier between us and nature – a pathway, a handrail – we’re saying we go here and nature goes there. That’s not how we’re meant to be as human beings.”

Dana Tomić Hughes, founder of design publishing company Yellowtrace says Australians are improving their exterior spaces and furniture retailers are taking notice. “Brands are waking up to this and releasing outdoor furniture.” Furniture makers such as B&B Italia, which recently opened a store in Sydney solely dedicated to outdoor pieces, are creating ranges that wouldn’t look out of place indoors. “The fabrics being used in outdoor sofas are waterproof but they don’t feel like plastic,” says Tomić Hughes. “And by making these products more tactile and elevated, outdoor spaces are more flexible.”

Adaptive reuse

Adaptive reuse – converting an existing structure for a different function instead of building something new – was initially about respect for our built heritage. More recently it became synonymous with sustainability and now it’s an economic imperative.

“Over the next 10 years or so there isn’t going to be heritage anymore,” says Haddow. “Architects are going to have to treat every building like it’s heritage and adapt and reuse. You’ll need a very good excuse to demolish something.”

The trend towards housing renovation is also being driven by location, convenience and a desire for people “to live closer to where they work rather than on a big block of land further out”, says architect Conrad Johnston, director and founder of Studio Johnston. “Because there’s a squeeze on accommodation, people are trying to adapt existing spaces into something that works for them.”

Architecture to order

To help facilitate the building of more homes in the midst of a housing supply crisis, the NSW government has reintroduced architectural pattern books. Part of this country’s building design history since the 18th century, the pattern books aim to accelerate new housing construction by providing home builders with template designs from leading architects for a fraction of the cost of commissioning a one-off design. Another effect will be to make the home building approval process quicker and construction easier, more affordable and sustainable.

One of the eight architectural firms chosen for the new housing pattern books was Studio Johnston, which created the Manor Homes 01. “Our design reimagines the classic four- or six-pack apartment buildings of the interwar period with modern living standards and sustainability,” says Conrad Johnston.

All the floor plans of the schemes can be adapted to a range of residents, from young families to downsizers. “About 98 per cent of housing in Australia isn’t designed by architects,” says Haddow. “By reintroducing pattern books, the state government is acknowledging that design is important.”

Repair and integrate

Reuse has also had an impact on the objects we put into our houses. Designer furniture retailers, such as Living Edge and Cult, have launched programs to buy back, repair and resell their products (or recycle if they are beyond repair).

Interior designer Sarah-Jane Pyke, creative director and co-founder of Arent & Pyke, says Australia didn’t always have a culture of repair and reuse when it came to furniture. “The idea of starting all over again with furniture when you move into a new home, with nothing from your past, is a little sad. It’s great we’re seeing reuse and repair at the retail level.”

The issue of long lead times for furniture has also forced designers and architects to devise creative solutions like built-in or integrated furniture. Pyke, Haddow and Johnston all say they’re getting more requests from clients and developers for items such as built-in sofas and banquette seating. “It’s back to the 1970s,” says Haddow. “Designing furniture that’s integrated into a space will become more essential not just because of the lead times and cutting down on transport carbon but also because it saves space in an interior.”

Designing with Country

Respecting and integrating First Nations culture into building design used to involve nothing more than displaying an artwork in the lobby but it’s now being embraced by architects from the beginning of the design stage. Sarah Lynn Rees, a Palawa woman from north-east Lutruwita/Tasmania, says the concept has developed into a more holistic connection between people, Country and the environment to produce culturally appropriate and sustainable outcomes that benefit all of a project’s stakeholders.

“It’s something that needs to influence every single part of a project, by engaging with Traditional Owners who can speak with cultural authority for a particular place,” says Rees. “It’s everything from how a building is positioned so it doesn’t impact the way water moves across the site to the materials used and the businesses and suppliers that are engaged with.”

She says designing with Country is now accepted practice in public and institutional building projects but the developers of multi-residential buildings are also engaging with it.

Art and craft

A growing emphasis on texture and tactility is emerging when it comes to the materials used in construction. “There’s a real shift to how things feel rather than just how they look,” says Tomić Hughes.

This change is in reaction to the design perfection promulgated by social media and recognition that the use of AI in image-making has blurred the line between what’s real and what’s (potentially) fake. “I think craft is back in a big way,” says Haddow. “The intersection of art and architecture is stronger than it’s ever been and there’s increasing investment in public art embedded in building projects. And that extends to craft as well and the question of where art stops and craft begins.”

The design of the Metro stations in Sydney is an example of the impact public artworks can have on the built environment. And a resurgence in the popularity of bricks illustrates how craft can be used in construction. “What’s driving the use of bricks is the sense of visual comfort and familiarity they offer,” he says. “People want to feel more connected to a place and bricks offer that. They’re textural, tactile and bring personality to a building.”

Start planning now

SEE ALSO: "How I Travel" With Interior Stylist Steve Cordony

Image credits: Julie Adams (main image of Gubi Al Fresco range); The First Church of Christ Scientist building in Darlinghurst by SJB Sydney; Anson Smart (Corunna House project by Studio Johnston); Richard Wong (The University of Melbourne's Atlantic Fellows for Social Equity Hub); Jackie Chan (Martin Place Metro)